Why cyberpunk icon Bruce Sterling believes that what’s happening right now is way scarier than anything in a sci-fi book.

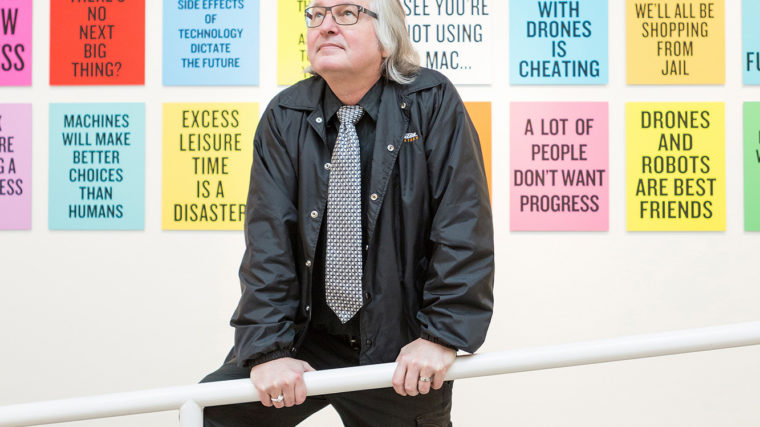

The current exhibition at Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein (Germany) is called «Hello, Robot – Design Between Human and Machine». One of the names on the extensive list of participants: Bruce Sterling (62). One the one hand, Sterling contributed an art installation, on the other hand, he worked as a consultant for the whole exhibition concept and wrote a new short story for the exhibition catalogue.

Sterling is the right man at the right place: Many of the things that we today take for granted have been anticipated years ago by this journalist, sci-fi-author, futurist and design critic from Texas. Sterling wrote about a digitally networked world long before the world was digitally wired. In «The Artificial Kid», he writes about a young man who makes a living from filming himself having bloody street fights, using remote controlled cameras.

The book was published 37 years ago (1980). In «Schmismatrix» (1985), Shapers fight against Mechanists – the latter use computer technology and artificial body enhancements. In «The Hacker Crackdown» (1992), Sterling reported on the world of organized Internet crime. Today, Sterling teaches at different universities and institutions and regularly publishes new stories. He mostly lives in Belgrade, Serbia.

TagesWoche met with Bruce Sterling shortly before the opening of «Hello, Robot» (exhibition until May 14th, 2017) at Vitra Design Museum for this interview.

Sterling’s video installation «My Elegant Robot Freedom» (2016). (Bild: Nils Fisch)

Mr. Sterling, through the years you’ve predicted many things and ideas that came to be true. What does that feel like?

Bruce Sterling: The moment a prediction comes true is not even the fun part – it’s when you predict something, and then it happens – and then twenty years go by. (laughs). I used to tell people that modems will become all-important. You remember modems?

I do.

I had to tell everyone about it: «Okay, it’s this box, and it’s a modulator-demodulator!» – «Why would I want something like that?» – «You can connect your computer to the telephone network!» – «Uh, first, why would I want a computer, and why would I want to put my computer on a telephone network? Isn’t this complicated? And wouldn’t that cost a lot of money?» – «No, you don’t understand! This is potentially a revolutionary situation. This will change people’s lives!» (laughs) Well, today it’s like this weird antique.

Another thing you’ve been telling people about is robots. Over ten years ago, you said: «Robots are just our shadow, our funhouse-mirror reflection» [paid article]. Why?

The term robot came from theatre, not from industry. It was made up by Czech playwright Karel Čapek. He was making a point about industrial production and the way workers are treated – automation and its de-humanizing and de-skilling aspects. So he has actors and actresses show up on the stage, dressed as machines, because you have to have a person faking the machine. A funhouse costume. There’s no robot there. Even R2-D2, the famous Star-Wars-Robot, had a dwarf inside.

Robot design has also been largely coopted by big business interests. Am I wrong in thinking there used to be more alternative design ideas making the rounds, thinking, for instance, of your ecological Viridian Design Movement?

You should think of these things in terms of transformational waves or cycles. I see waves of that stuff going on in robotics. And robotics has its charm because most of it is impossible and stays in the fairy land. Design fiction. But now we’re getting into a stage, we’re approaching an industry of remote controlled, very capable, wireless broadband sensor-actuated networks. They just move things, they deliver things, they spy on things, they assassinate people, they turn switches on and off, they can control volumes, they can fetch things for you from the internet… so we’re going to have robots with the cloud for brains.

This huge remote-controlled network you’re describing …

…yeah. The internet of things (IoT). Although I think we’re going to get a balkanized internet. We’re going to get silos of things.

Does the IoT have the potential to make its users dependent, to enslave people?

Well, it won’t enslave them. If they’re going to be enslaved, they’ll be enslaved by the people who already own everything. People might be in debt. And they might be under surveillance. If you’re on Facebook, you’re under surveillance already, pal. They know more about you than a secret service ever will. (laughs) And you’re submitting to that willingly. It’s too hard to call that slavery. It’s very hard to be really free. That’s like Robinson Crusoe. Very isolated. It’s not very much fun.

An old idea is getting some traction again: The «singularity», the claim that one day an artificial super-intelligence will come into being, making everything unpredictable. This so-called technological singularity will suddenly change everything that was before.

I think it is bunk.

You’ve also compared it to end-of-the world beliefs – apocalyptic longings.

I’m a singularity sceptic. It kind of works as an artistic idea: You get great poetry out of the end of the world. Milton’s «Paradise Lost». It’s like Philip Beesley with his installation upstairs: He’s very much into the hylozoic – he wants to do artworks that look alive, that are mechanical, and yet possess some form of life. In my view, the singularity is a mythical idea, but not practical. I like the art, for instance Beesley’s – but it’s not alive, it’s not intelligent, it’s an interactive installation. But it’s so much like a thing that’s alive and intelligent: It’s like seeing a portrait of your wife that’s more her than her. Like, «okay, that’s not your wife, she’s not going to make you breakfast, she’s not going to have your children, but you’re still happy that it’s there. Even though it’s an illusion.»

«I think of myself as a guy with a dark side. But it’s not much darker than every day life in Belgrade.» (Bild: Nils Fisch)

Does that mean you believe humanity will stay in control of technology?

No… I don’t know. We’ve had a meeting recently in Germany. A bunch of guys from the luxury communist movement.

Luxury communism?

Luxury communism meaning «ok, if we’re going to automate everything, why don’t we make it very nice for everyone». So you’ll have like this tiny group of people running the machinery and the rest will have annual income, shelter and food.

Would this work, in your view?

If we wanted to scale back, we could afford to do that. If we’d wanted to live in Basel like people lived in Basel around 1915 – you know: Just a few sets of clothing, small housing, not a lot of air conditioning – people wouldn’t have to work, they could be free and do what they liked, read, have children, whatever. You’re not going to have servants. The world would be pared back in some ways.

But would people want to live that way?

I could cheerfully live that way. But I’m a novelist. And I have a little mountain house in the Balkan hills, where life is quite primitive. And I really enjoy it there – I read poetry, go for long walks. I’m from Texas, I don’t mind it. I don’t mind camping, tents, boiling your water. But that’s not for everybody. And in some ways it’s delimitating. But maybe that’s not the worst problem about it.

Which one would that be?

Having very little ambition. So now I got all this stuff, and now I’m supposed to do nothing? Like, what’s at stake for me? I’m not sure if this would really work. Humanity would be in control in that situation. If we cut way back in terms of pollution and a much more sustainable economy, we’d be in much better control of our affairs than we are now. But there are other problems with it that are not well thought through.

Such as?

If you’re living in a green, sustainable village: What if Al-Qaeda shows up? What if they just come into town with pick-up-trucks and machine guns and kill half of you and take all the women? Now what? I guess we’ll bury the dead! Annihilate those sons of bitches? Oh, can’t do that. No capacity, no tanks, no rockets, no satellite surveillance. Kind of helpless, aren’t you? You’re not a very well-armed society, you can’t push anybody around. You didn’t have any reason to fight before, you don’t have ambitious generals who want the medals… You might be like Fiji-islanders suddenly attacked by Europeans. Who knew?!

Your Sci-Fi work obviously covers dystopian ideas – do you share them, personally?

It’s a matter of temperament. I think of myself as a guy who has a dark side. It’s not really darker than normal life in Belgrade. I live there, some of the time, I’m married to a Serbian woman, and I have a lot of friends there. To them I’m a remarkably cheerful guy: «Ah, your American husband, he’s so funny, always smiling! And so practical! We’re sitting here drinking, and he always wants to fix things, always makes suggestions.» In that society, I am a kind of a Pollyanna figure. People consider me very upbeat, very optimistic. In American society, I’m a guy with some very odd interests. I used to write crime journalism. It takes a toll on you to hang out with people who are criminals and with cops.

Crimes are increasingly committed online. Your book «The Hacker Crackdown» (1992) on Internet criminals turned out to be rather prophetic.

Oh yeah. I wish it had been more sinister than it was, because at the time it seemed very exaggerated – especially the amount of theft already happening. It’s so much worse now!

The book ends on this kind of bitter-sweet note, that now, the professionals are taking over. Cleaning up the Wild West of the World Wide Web.

They didn’t do that great of a job. It’s bad. Organized crime, you now have vast, state-supported mafias robbing hundreds of millions of dollars. They’re trying to seize the state in a lot of places. There’s a major F.S.B.-scandal at the moment.

Go on…

Guys, holed up with their heads in bags. What the fuck went on there?! My rumours say that they tried to blackmail Medvedev by showing them that they had stolen his emails. What the fuck kind of operator goes to the head of state and says: «Remember what we did to Hillary? We’re going to fuck you over until you pay us.» Where did they think they were gonna go? To Fiji? Tahiti? I’m absolutely baffled by that.

Baffled? You?

What’s happening is far more dystopian than most of the stuff I’d put in a sci-fi book.

__

«Hello, Robot. Design between Human and Machine», Vitra Museum, February 11th – May 14th.